In talking with product stewardship and risk management professionals, we occasionally see a fear of too much knowledge. You may believe that knowing about a specific risk means being held legally responsible if the risk manifests. Unfortunately, that’s true.

Proving liability when a harm results requires showing that the risk was reasonably foreseeable. And known risks are by definition reasonably foreseeable. In product liability cases in particular, a manufacturer has a duty to warn consumers of any risks that it knows about or reasonably should know about.

But there is more: Not knowing about published science is not reasonable.

US courts have found that the duty to warn includes both actual knowledge of risks and constructive knowledge based on available scientific literature. This is true whether or not the defendant is actually aware of specific scientific literature describing the risk.

In effect, courts have placed a seemingly impossible burden on your company to monitor the tens of thousands of peer-reviewed scientific articles published every year on the chemicals and materials you use and produce.

With big data, that requirement becomes easy.

You may worry that using monitoring tools like ChemMeta will create an audit trail showing actual knowledge of risks. But the legal standard already imparts constructive knowledge of these publicly available and readily accessible sources of scientific literature. Hiding your head in the sand is no defense at trial.

In fact, big data can create opportunities for affirmative defenses.

If you manage product stewardship in a strategic way, you can reduce the chance of tens of millions in punitive damages.

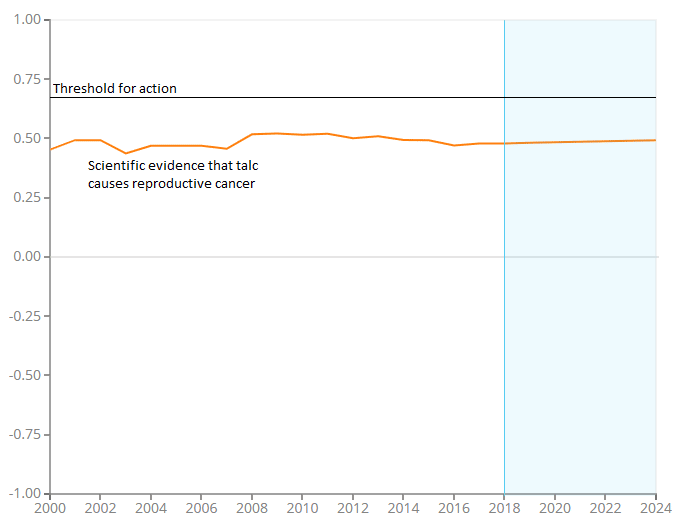

In cases like the recent talc litigation where the available scientific literature does not show strong evidence of a risk, using a tool like ChemMeta can actually lower the likelihood of punitive damages because you can show that you were relying on:

- an objective, independent source;

- that takes into account all the peer-reviewed scientific literature on the subject;

- and tells you that the evidence of the risk was not significant enough to worry about.

In the case of talc, our algorithms have analyzed the science over the last twenty years, and the scientific consensus that talc causes ovarian cancer has never risen above a hypothetical threshold for action (e.g., for providing a warning or considering substitutes). And many other widely used products have had worse predictions over the same time period.

If the defendants in the talc litigation had been relying on this information and pursued a product stewardship and safety strategy based on ChemMeta thresholds, the likelihood of punitive damages could have been significantly reduced.

Get in touch with us today for a demo of ChemMeta, and start managing your product stewardship risk in a systematic and strategic way.